|

On Steven Carrelli

Containers, distances, shadows, and associative thinking, the poetry of solid objects, the surrealism in slightly altered perspective, measurement, mathematics, displacement...a sense of intransigence. Bags, all those bags, and packages deprived of natural light, seemingly in media res, but arrested. The space between the objects in Steven Carrelli's work is time, not only temporal disjunction, but the way time inheres to things, to lines, to texture, to almost obsessive detail that brings the object to life, but also brings us to the sense of time etched in process.

In "Improvised Landmarks" a toolbox looms in the foreground, architecturally, while some distance away (what is distance?) is...what? A miniature Brunelleschi dome covered a la Christo? A very unhappy kumquat? Is it a large lunchbox, after all? No. In the background, the outlines of a wooden wall, barn-like, incomplete, its lines stretching like a web out toward the lunch box, establishing connection. A long shadow points from the box to the draped object. It points. What's underneath is a conception that requires opening one box and lifting a veil. That tools are landmarks shouldn't be lost on us, as we think about the way the light hits the side of the box responsible for everything - how bright it is, how impossible the necessary wash of the front.

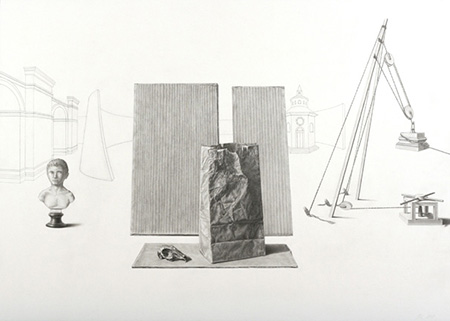

In "Ruins in Progress" my first response is "rebus": Bust and paper bag and cardboard and skeletal head and primitive construction crane invented by Filippo Brunelleschi, and the word is...My second response is that the bag (school lunch?) and the small skull are on stage. Everything's a ruin. You are. Filippo Brunelleschi? Don't ask. What's in the bag? A cathedral, a sandwich? What's in the cathedral? A mouse, a bag. And I'm bothered by the shadows, that seem brief, rather than short. The light has an internal dynamic that is slightly maddening. Tiny memento mori shadow of the skull, the lunar shadowing of the bag, the sideways shadow to the edge of the canvas of Filippo Brunelleschi's crane. Stare at the line down the middle of the bag - reusable, disposable - do we put the skull inside? - a question mark almost forms. And who is the figure of the small sculpted bust? Our small implacable double gazes out over our shoulder. He's bag sized.

And sometimes, even the shadow of a bag is alive. A bag that's seen better days. A shadow that's curious. An unmarked mag. A shadow marking time. A shopping bag, creased most heavily at the bottom, and lined widely further up. How can the handles have stayed so jaunty? The shadow's a virtual tourist of light; it's a slightly ominous cat, eminently ready for its next move.

"Location with Views" is the Northern Renaissance through a looking glass. Or a mirage, the outline of historical desire. Are we thinking about a room with a portal? Is the past, is painting, is the history of art an Étant donnés? Are we seeing what we shouldn't see and know we must? There is the sense in Steven Carrelli's work that we are seeing what we have to see, though we frequently haven't ever seen these things before: these bags, these views to another time, these little cathedrals.

|

On Louise LeBourgeois

We’re always mountaineers in a misty landscape, everything we look at might overwhelm us or transport us. But serenity seems like a postmodern concept. The moon and the sea, classically sublime subjects, ask us here to consider where we are; the clouds, vessels of light, seem textual. So we’re exploring place, and it seems very familiar. But to think we know what we’re gazing at would be a terrible mistake. Louise LeBourgeois paints us into a corner, where the image overflows with a haunted and all but unknowable context. Then we see the levee.

In “Luna Piena,” the moon is a piece of rotten fruit, floating ethereally, but it seems to generate its own light. Night light. The almost blue of black isn’t space, as in “outer” at all; it’s night, conceptually. Underneath, beneath, clouds or vapors. Impossible. But everything that rises must converge, and this immanence disturbs me.

That all things are in motion, that motion and stillness can somehow combine. “It seems that there are movements, some natural, others feverish, in these great bodies, just as in our own” (Montaigne, “Of Cannibals”). We see water in movement and register this as sensation.

The implications of light are only partially answered in their figural reflections.

“All the reasons for light are obvious.” Eric Fischl, writes. But where is it going, and where does it stop? And is this equally true for color?

Double vision of the repeated landscapes: what am I seeing, what was she looking for, what am I looking for, what was she seeing?

Landscapes always disturb me. They’re always prefiguring death (when they’re not figuring death). The sensation of movement that is almost and is past, which creates a space analogous to memory. But it’s not ours. It’s unfamiliar, so it becomes a dreamscape. I experience all landscapes as dreams that someone else has had that I have somehow imported. Here, the horizon lines pull away and under the clouds, or they seem to be asking me something. That the answer may be in the water unnerves me. I dropped my watch in the water. I broke the surface.

Memory and illusion are bedfellows when an image asks us to enter its spell, the dialogue with the real that isn’t real. Eventually, Dorothy says, “But I want to return to the real.” The real real. I’m talking Kansas. Says, the Scarecrow, “Get real, even that’s a dream.” Painting makes Kansas complicated.

What is a real imagined space, after all? In the space between what Guy Davenport called the geography of the imagination and the real geography of the painted subject is the conjured image, marked by the real, but not bound by the real.

Louise LeBourgeois’s landscapes seem fiercely displaced, the point of view estranged, or strange. The colors of sky and clouds and rocks are merging too harmoniously—the viewer turns to the dark spot in the water for relief from what should be . . . serene. The moon is surrounded, brilliantly, by a Hubble-like firestorm of clouds. Where are we to see such a thing? It’s breathtaking, and makes me anxious. And the water paintings, the heart of her work. The horizon line and water levels at the viewer’s eye are crucial to the paintings’ emotional valence.

The trees in the distance are evaporating because perspective demands they do, in specific places, when memory is ripe enough.

David Lazar is a Professor in the English Department and Director of the Nonfiction Writing Program at Columbia College Chicago, and he is the editor of the literary magazine Hotel Amerika. His books include Occasional Desire, The Body of Brooklyn, Conversations with M.F.K. Fisher, Truth in Nonfiction, the prose poetry collection Powder Town, and Essaying the Essay.

|